Peat extraction does take place in previously undrained areas

An in-depth investigative journalistic study reveals what the peat lobby furiously denies: Peat bogs are freshly drained for peat extraction. The fairy tale that the peat used in gardening and horticulture only comes from previously drained agricultural land with little to no ecological value is impressively falsified.

This is an inofficial translation by Philipp Gramlich. The original article was published in the Sueddeutsche Zeitung (26th January 2024, original article). Published curtesy of the authors Nathalie Bertrams, Ingrid Gercama, Tristen Taylor.

Dug off

Peat will soon no longer be mined in Germany. But we are already importing the valuable material from the Baltics.

And destroy the moors there.

It has already reached many people in Germany: When planting on your balcony, it is worth looking for the “peat-free” sticker on the potting soil in the hardware store. Because peat comes from moors and moors need to be protected. But the cucumbers and tomatoes we eat still mostly grew on peat. Where does this peat come from? And is a peat-free life even possible in Germany?

Elbu raised bog in Estonia

With squeaky rubber boots, Liis Keerberg trudges through the still untouched central part of the Elbu bog in southern Estonia.

Here, carnivorous sundews glitter reddishly between peat moss and open water areas. In spring, cotton grass transforms the landscape into a sea of white flowers in which marsh birds such as golden plovers, dunlins and cranes nest.

“This moor could be destroyed so that Germany can get our peat,” says 45-year-old lawyer Keerberg.

The idyll is threatened.

Hiiu Turvas, a company with German owners, plans to drain the bog for industrial peat mining. Liis Keerberg has filed a lawsuit on behalf of the Estonian Ornithological Society against the government that approved the project. Now, the future of the 7,000-hectare bird sanctuary lies in the hands of the Supreme Court of Estonia.

“Whether or not it is legal to allow peat extraction in pristine bogs will be a landmark decision,” says Keerberg. “Because instead of renaturalizing moors, we are digging up more and more.”

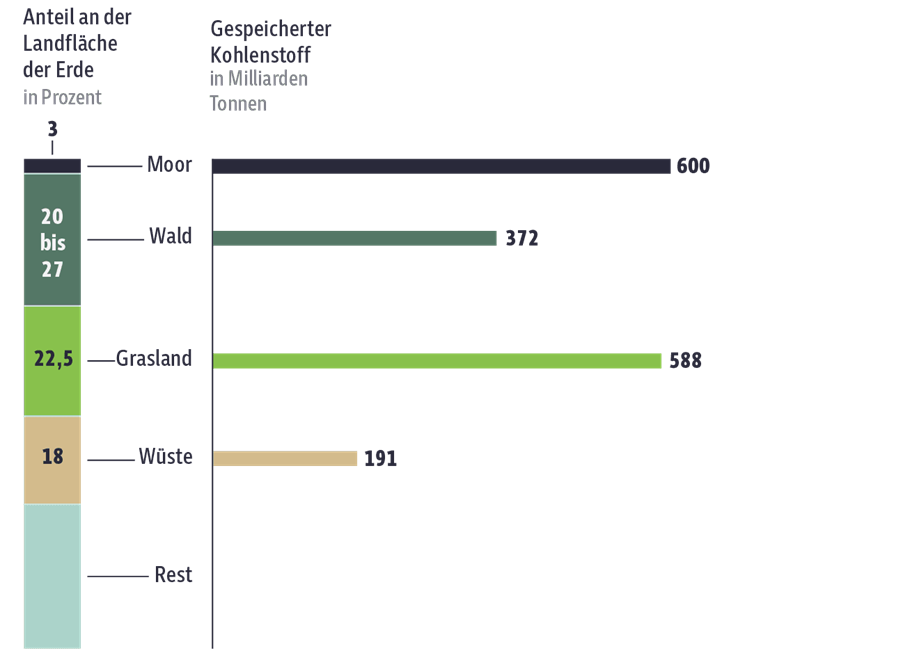

The Elbu Bog is not only important for bird protection and species protection. Huge amounts of carbon are also stored under its green-brown moss cover. Peat is a fossil resource that forms over many thousands of years from incompletely decomposed, dead plants in the absence of air. Although peatlands make up only three percent of the Earth’s surface, they store a third of the world’s total carbon – almost twice as much as all of the world’s forests as long as they are intact.

However, if peatlands are drained or mined, the carbon bound in the peat soil is released into the atmosphere as CO₂. This now accounts for five percent of all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide.

In Germany, 95 percent of the moors are currently drained. Agriculture is practiced in most of the drained areas; peat extraction is a relatively minor problem in terms of dimensions – and one that is also being phased out. Since the 1980s, only degraded and drained agricultural areas have been allowed to beextracted in Germany. However, there is virtually no natural moor left that could be developed.

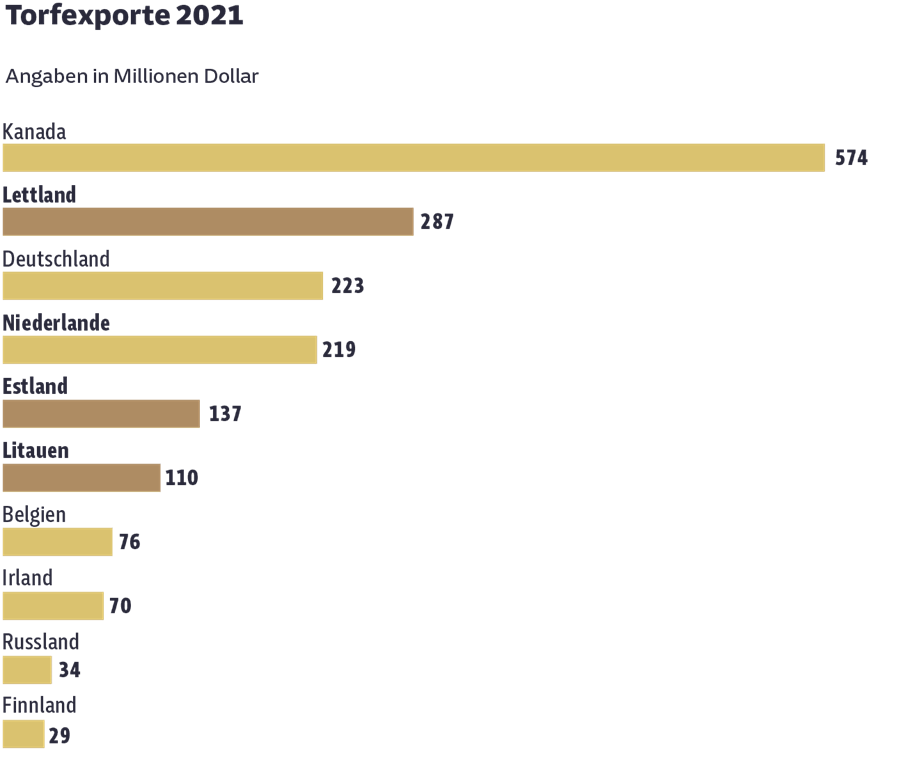

In a few years, peat mining in this country should be completely history. No more mining licenses will be issued, and the old, time-limited licenses are gradually expiring. However, we still use peat because many plants grow best and, above all, fastest on peat. And that’s why it’s imported – for example, from the Baltics. Currently, around 5 million cubic meters of peat are mined in Germany every year. Roughly the same amount is already being imported today, mainly from the Baltics.

A total of 4.4 million tons of peat are mined and exported in the Baltic states every year, and natural moors are also destroyed. Germany and the Netherlands are the largest importers of Baltic peat, used for potting soil from garden centers and growing media in industrial vegetable and ornamental plant cultivation. A lucrative business. “Industrial colonialism is taking place here,” criticizes Keerberg.

Holland: No food without substrates

The Westland region in the province of South Holland is known as the “Glass City.” Behind the fogged windows of hundreds of greenhouses, millions of seedlings thrive in peat substrates.

The Dutch are considered global technology leaders in the greenhouse cultivation of vegetables, flowers, and ornamental plants.

The key to this success? The development of growing media based on peat.

They enable high-performance horticulture that creates optimal growth conditions for plants through minute-by-minute temperature, light, and irrigation systems.

The Netherlands exported over 5 million tons of vegetables in 2022 alone. Almost a third of this ends up in German supermarkets. Consumers, therefore, almost cannot avoid consuming peat indirectly.

“Without substrates, there is no food,” says Han de Groot from the Dutch Association of Potting Soil and Substrate Manufacturers (VPN) categorically. The industry representative explains the advantages: Peat is perfect for seedlings and young plants. It stores water like a sponge and releases it when needed. It is free of germs and pathogens and has a constant, low nutrient content. Some plants, such as mushrooms, lettuce, and strawberries, cannot be grown without peat, says de Groot. [Remark by the translator: this is wrong information, soft fruit are successfully grown peat-free in the UK. The authors of the article have confirmed that this German quote of the Dutch original quote of Han de Groot has been mis-translated in the editorial process. Han de Groot didn´t make this factually wrong statement] By 2025, however, the industry will “double the use of renewable raw materials” and supply “100 percent responsibly sourced peat”. More precisely, this means: You want to adhere to national and EU laws when mining, take climate and environmental protection into account, and restore the mined areas as far as possible.

“As far as that’s possible” – it’s not just this restriction that makes biologist Karin Bodewits in the Gelderland village of Oosterbeek shake her head.

Together with her husband, she founded the organization Stichting Turfvrij, which calls for a ban on peat in the Netherlands. In her opinion, the substrate industry is not concerned with European food safety or green cities, but with its own profit margin. “The industry is trying to discredit scientific evidence. They act like it’s not as destructive as it actually is,” Bodewits says.

Two-thirds of the Baltic peat is used to grow potted plants, flowers, and ornamental shrubs, i.e., not essential things. “It’s pure convenience to use peat. It’s nice for the customer that they don’t have to carry so much weight around the store,” says Bodewits. “But for ornamental plants, it’s a complete waste.” This also applies to basil pots from the supermarket: “These are disposable plants; we only use them for one meal. And then we throw the peat in the trash.” This means buyers are jointly responsible for the climate crisis and destroying valuable biotopes. She asks, “If it can’t grow without peat, do we even want these products?”

Estonia: The dirtiest industry

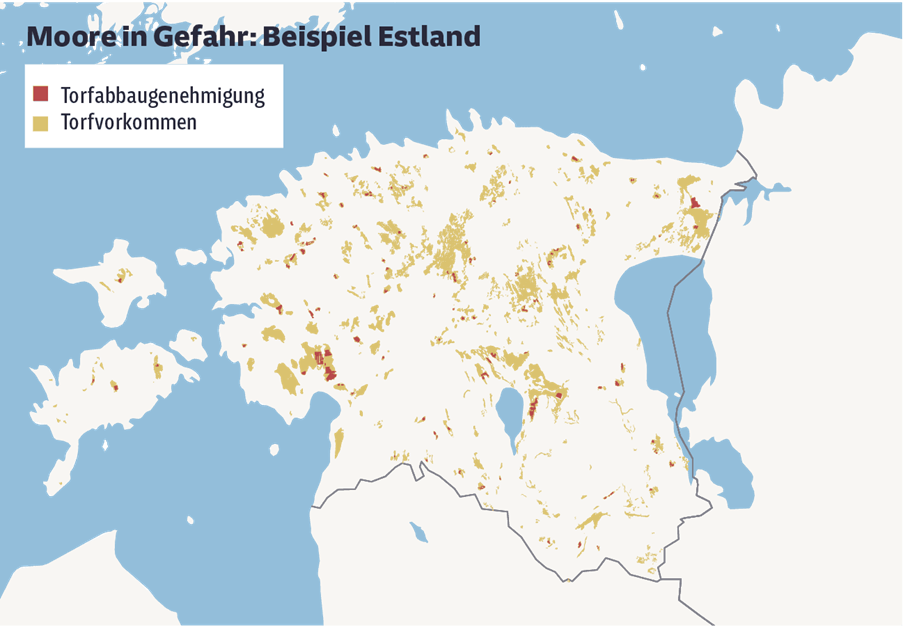

In Estonia, up to 1.5 million tons of peat are currently mined every year on an area of 20,000 hectares. In 2016, the entire moor area was mapped, and 150,000 hectares were identified for potential peat production – a kind of shopping list for the industry.

Marko Kohv, a geologist and peat specialist at the University of Tartu, says:

“The peat industry is, together with shale oil production, the dirtiest industry in Estonia. We know it causes huge emissions but doesn’t create many jobs. So why are we doing this?”

Kohv is worried because the number of permits applied for for peat mining has risen sharply in recent years.

Over twenty percent of Estonia consists of moorland, and industrial peat mining has already damaged more than two-thirds of the wetlands.

For horticultural growing media and potting soil, the industry needs white peat, the slightly decomposed and exceptionally absorbent peat from the top layer of the moor. In order to dismantle it, new areas have to be developed, and moors opened up, as only the first 5 to 15 centimeters are used – as can be seen here in the foreground.

The black peat underneath is then excavated meters deep. The regeneration of wetlands takes an incredibly long time: in healthy, moist moors, peat grows on average around one millimeter per year.

A tenth of global peat production comes from Estonia, and all three Baltic countries account for a third of production. It’s no wonder that the Baltic states are also among the world’s most important exporters.

Peat mining is responsible for ten percent of Estonia’s total CO₂ emissions, says the Estonian Climate Ministry, more than all of the country’s cars and trucks combined. Industry experts believe this calculation is exaggerated – the EU calculates the emission levels that peat releases when it is burned for energy, which is now banned almost everywhere.

In Germany, at least potting soil for private consumption, i.e., garden centers, should be completely peat-free by 2026. The Thünen Institute in Braunschweig has calculated that this alone would save 400,000 tons of CO₂ annually. By 2030, the substrates for commercial horticulture should also be largely replaced by renewable raw materials. However, these requirements are not binding, but are on a voluntary basis. And no one knows precisely how this is supposed to work or what the peat could be replaced with in such large quantities.

The existing alternatives also have disadvantages: Compost is more interesting for the hobby sector – it can only be used to a limited extent for high-performance horticulture because of its variable quality. Coconut fiber, a waste product from coconut milk production, is ideal for plant growth. However, this material comes from tropical countries like India and Sri Lanka and is controversial because of its water and chemical consumption. Wood fibers, the most important substitute material in the professional sector, have been very expensive, especially since the Ukraine war, as they are also used to generate energy.

A ray of hope could be the large-scale cultivation of peat moss on rewetted moor areas, says Philip Testroet from the Garden Industry Association (IVG). Raised bogs consist largely of decomposed sphagnum moss that grows on the surface. The plants can store large amounts of water in their cells and are, therefore, perfect as a peat substitute for substrates in horticulture.

In raised bogs that have already been cleared of peat, these mosses can now be grown after rewetting. If 35,000 hectares of drained raised bogs in Germany were rewetted and used this way, it could replace the annual requirement of three million cubic meters of white peat (weakly decomposed sphagnum peat) in Germany.

In Lower Saxony, where the majority of the last peat mining areas in Germany are located, people are already experimenting with this type of paludiculture, i.e. farming on wet areas:

Sphagnum moss cultivation on extracted peat bogs

In order to implement this on a large scale, cultivation would first have to be made attractive to farmers, says Testroet. In addition to subsidies for agriculture on rewetted land instead of drained land, investments would be needed in the trading chain in order to get the biomass into horticulture. Testroet doubts this will work on a relevant scale in the next ten years. Whether enough moss can be produced and whether cultivation is profitable is questionable.

Merten Minke from the Thünen Institute believes the will to change is present in politics and business. In his opinion, the biggest problem is the still very high price of peat substitutes, which currently cost around ten times as much as peat. If the environmental costs of using peat were taken into account, he says, peat would be significantly more expensive. Morally, it is not right: “We stop peat mining here and get the peat from somewhere else. This is how we shift the problems to other countries. We must stop the destruction of peatlands everywhere.”

“Peat is a cheap material – because external costs such as CO₂ emissions, water problems, and lost biodiversity are not included in the price,” says Marko Kohv in Estonia. In the Baltics, mining is extremely profitable due to low rents and wages and inadequate nature conservation regulations. The costs of restoring peated areas are not included in the price, and the production process is simple and highly mechanized. “All you need is an excavator,” says Kohv.

“And the profits go to the foreign owners.”

Many international companies have now moved their peat production to the Baltics.

Dutch companies dominate in Estonia, and in neighboring Latvia, more than half of peat production belongs to German owners. Chris Blok from Wageningen University in the Netherlands predicts that global demand for peat will quadruple by 2050. By 2030, China will also need 35 million cubic meters – almost all of the peat currently available worldwide. China is now increasingly relying on greenhouse cultivation to feed its 1.4 billion inhabitants.

Estonia: The tricks of the industry

What remains of a bog once the peat has been completely removed can be seen in Estonia. Marko Kohv is a geologist; he is running across a bone-dry field.

Nothing is still growing on the Tähtvere Moor, cleared of peat for fuel during the Soviet period and has remained fallow ever since. Only a few small birch trees, whose roots have been exposed by the wind, are looking for water.

Nature has not recovered here even after three decades, explains Kohv, letting a handful of dark earth trickle through his fingers.

The bare peat layer is highly flammable. “Most former peat-growing areas are in roughly the same condition,” he says.

Actually, according to European legislation, moors that have been removed from peat should also be rewetted in the Baltics. However, many companies use a simple trick to avoid or postpone repairs.

After their license expires, they can apply for new permits for adjacent areas, thereby extending the obligation to renaturalize for another 25 to 30 years. The producers make the profit, but they outsource the costs.

The Estonian government is currently rehabilitating 2,000 hectares of drained bogs from Soviet-era peat extraction. According to the Climate Ministry, 13.35 million euros have been invested in wetland restoration so far, largely funded by the European Union.

“So it is German and Dutch tax money that flows to Estonia to solve the problems of the peat industry,” says Kohv.

Latvia: Measurement for the future

In the neighboring country of Latvia, an hour’s drive from the capital Riga, Māra Pakalne and two colleagues from the State Forestry Institute are measuring CO₂, methane, and oxygen emissions in the wetland in the Ķemeri National Park.

Researcher Pakalne from the University of Latvia is responsible for the EU Commission-funded “Life Peat Restore” project, restoring raised bog habitats in Europe.

She and her team carry out studies in restored and semi-natural moors like here, measure greenhouse gases, and compare the results before and after rewetting.

The few moors in Europe that are still genuinely natural, many of which are still in the Baltics, are more than climate-protecting carbon sinks, explains the Latvian biologist.

Intact moors regulate the water balance, serve as a filter for clear drinking water, and help with both drought and floods. They cool the local and regional climate and are a habitat for rare and endangered animal and plant species. But they can only do all of this if they have never been drained in the first place.

The attempt to remediate drained bogs, as can be seen here, is also very complex.

“If you destroy the peatlands, you lose all the biodiversity,” says Pakalne.

It is impossible to completely restore the natural vegetation after peat extraction. “You can stop CO₂ emissions through rewetting and also establish some species. But you won’t get the natural floodplains, depressions, moorland hills and all these fantastic landscapes that have developed over thousands of years.”

Liis Keerberg, a lawyer in Elbu Moor, Estonia, agrees with Pakalne. “It’s about whether the government keeps its promises to protect our nature,” she says. “The area is home to valuable habitats and species. The question is whether Estonia is responsible for preserving these values or not.” Keerberg cannot understand why the Estonian government allows pristine moorland to be destroyed.

“Peat belongs in the ground, not in a bag,” she says.

The research for this article was supported by Journalismfund Europe.